Growing a Carbon Forest

While any tree planting will sequester some carbon by taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, the volume of growth of little trees is so small that it doesn’t accomplish much in its early years. For example, planting 1” or 2” ball and burlap trees 8-10 feet tall may appear impressive, but they require 2 or 3 years to recover from the shock of having most of their root mass cut off to create the transplantable root ball. This also leaves them vulnerable to desiccation and needing lots of care for several years. In the meantime, a seed planted at the same time can often put down a taproot and send up a shoot, which in 4 or 5 years will nearly catch up with the B&B specimen of the same age, and will have roots that go deeper than the nursery ball regrowth and be less vulnerable to windstorms and drought.

For obtaining a lot of woody mass quickly, above and below ground, with minimum labor and cost, I developed the technique of “willow jetting” in the 1990s. Originally intended to supplement streambank erosion control projects, it can also grab a lot of carbon quickly. Ten foot tall dormant cuttings of sandbar willow can be harvested, pruned, and bundled for transport. With my high pressure water jetting tool, they can be planted 5-6 feet deep. A team of four can harvest and bundle 1000-1500 cuttings per day, and can deep plant 1000 per day. In the right soils, they will quickly grow roots all the way down, and sprout new tops above most weeds, and pretty much fend for themselves. A paper that graduate student Rick Langel and I published in 1999 is available as a PDF with more details. I still have the jetting equipment and it is available for Bur Oak Land Trust’s use.

Rick shows the jetting tool, note the 3 water jets that bore the planting hole.

The high pressure pump sucking water from creek. Lid removed from protective box to show pump.

The tip of the jet pipe.

These 1200 dormant willow whips, tied in bundles of 50, were brought in my yellow carryall in one trip.

Two teams of two each jetting in dormant willow whips, pump in box between them.

Willow whips leafing out along creek with an understory of seeded oats.

Rick digs up recently leafed-out willow whip to learn that it already is also growing roots.

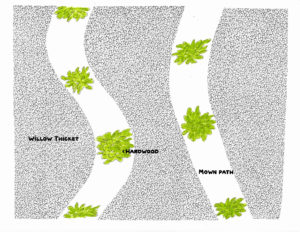

My proposal today is that Bur Oak Land Trust, or others, could plant a “carbon forest;” one designed to get carbon sequestration underway immediately with the willows, while other young and slower-growing tree species gradually catch up with and overtake, and eventually shade out the willows. While they grow and sucker rapidly, sandbar willow is always a small tree and dies young. An easy maintenance planting schematic is proposed below:

The site required for this proposal would have moist soils but not be too prone to flooding. The willows would be planted about 5-6 feet apart and expected to fill in more densely by suckering. The wide mown paths would be maintained by regular mowing. Within these paths seeds or seedlings of native hardwoods would be grown. I suggest a mix of the faster growing species like silver maple, pawpaw, and basswood; and slower ones such as swamp white oak, northern pecan, and shellbark hickory. With a zero radius mower, little weeding would be necessary.

In about 15 years, the willow will start failing and if necessary hardwood seeds could be planted in the larger gaps. Black walnut is especially aggressive in this setting.

If Bur Oak Land Trust is interested in developing its own carbon forests, which will also have value for wildlife, recreation, etc., this year could start with prepping a test plot, planning a water supply for the jetting tools, locating a donor patch of sandbar willow, and developing a protocol for actually measuring or at least estimating the amount of carbon sequestered annually.

And the Trust might decide that traditional management of traditional conservation properties is a better use of its resources, and leave the test plot approach to County Extension and University science departments. Perhaps there is room for a cooperative venture here with a university student launching the carbon study, perhaps someone on the AmeriCorps team who wishes to go into carbon management. There are several possibilities.

Tags: carbon sequestration, Lon Drake