Building Wetlands Efficiently

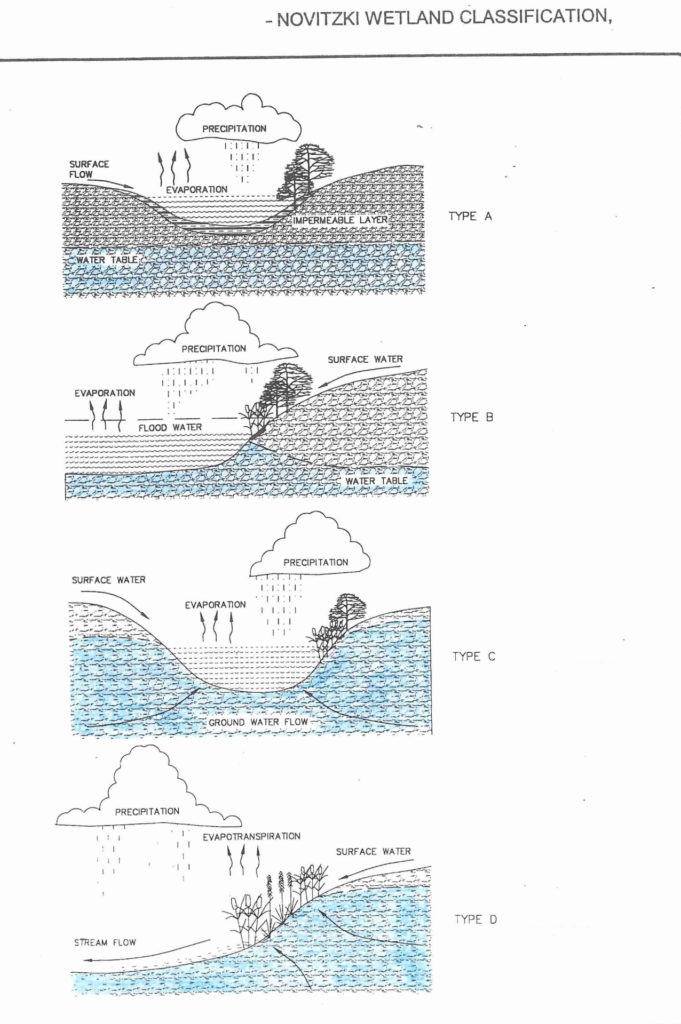

The construction of a wetland is mainly an earthmoving exercise, reshaping the landscape so that water will be provided as surface flow, or groundwater inflow, or both; and it will be retained for a while. The four main combinations usually available are illustrated with the cross-section sketches that follow (copied from Novitzki, 1979)

The construction of a wetland is mainly an earthmoving exercise, reshaping the landscape so that water will be provided as surface flow, or groundwater inflow, or both; and it will be retained for a while. The four main combinations usually available are illustrated with the cross-section sketches that follow (copied from Novitzki, 1979)

When you are doing wetland design, one goal is to balance the “cut and fill.” “Cut” refers to the amount of dirt you need to remove, and “fill” means the amount you need to put back somewhere so that it will also be useful, and not too far away from where you got it. So at a very local scale you might do best to design little wetlands in pairs – one that produces excess dirt, and the other to use it. Here is a pair of examples on our little acreage in western Johnson County:

The fill wetland. Note the zoned vegetation, controlled mainly by water depth and frequency of flooding.

Our fill wetland was created by making a little dam across a somewhat overdeepend valley, overdeepend compliments of a century of abusive farming. The dimensions were staked out and measured simply using a carpenter’s level and a long tape measure. Its watershed is about an acre, including our roof runoff, which proportionately adds much more water than a similar-sized patch of well-vegetated watershed. Only in very wet seasons, like spring 2019, does the water table rise high enough to be above the floor, and the wetland therefore gains groundwater at these moments.

Native wild iris scattered through native sedges in the cut wetland.

About 500 feet away, at the base of a nearby hillslope, I designed another wetland as a cut notch with a level floor, which also had about a one-acre watershed that included most of our driveway runoff. Using the same tools and methods, the cut was initially too skimpy to supply enough dirt for the fill dam, so I enlarged the design a bit to balance them out. Then in order to retain a bit of water for a while, the cut wetland design included a raised lip originally a foot high, which has today, 30 years later, settled to about 9 inches. Like the fill wetland, groundwater normally plays a minor role here in most years.

The actual construction was done by a local guy who had a trackhoe and a dump truck. The two wetlands were close enough that after every 4 or 5 truckloads were moved, he could shuttle over with the trackhoe and smooth and compact the growing fill dam.

Both of these wetlands often go dry in mid-to-late summer. This favors the little frogs – the chorus frog, cricket frog, and our two tree frogs, which only need a couple months of open water to complete their life cycle of egg-tadpole-adult. The big frogs – green and bullfrog – will eat small frogs, but need two springs as tadpoles to complete their cycle, so wetlands drying out in midsummer break their cycle. When the water gets shallow enough, great blue heron and little green heron move in and feast on the large tadpoles. If any are left when the wetland dries out, those also perish.

So if you are planning a wetland construction project, think about how you will utilize all the dirt that needs to be displaced and turn it into something useful, perhaps another wetland.

Another design option is that if you are building a wetland in a valley, you could keep widening out the valley making a wider wetland until you had enough dirt to complete the dam or berm that is going to contain it. Referring back to my wetlands in relation to the Novitzki diagrams, both of them are – Type A most of the time. Only during an especially wet season, like spring 2019, does the water table rise enough to briefly make them Type B. All the vegetation in the two wetlands was originally planted as wide-spaced transplants, and with a bit of annual weeding has completely taken over in their new home.

Tags: Lon Drake, wetland construction, wetlands