Big Meteorite Impacts, Part I: The Lunar Reference

In my blog “Stardust” from September 12, 2019, we considered the steady rain of small meteorites which enter our atmosphere at high speed, mostly burn up, but produce tiny blebs of stardust that today we can separate and identify from the much greater masses of earthly dust and debris. Today, let us look into the effects of the really big meteorites which have crashed into Earth and our moon.

Because our moon has lacked running water, wind and plate tectonics for most of its history, many impact craters on its surface have been barely modified over geologic time with the main disturbance being later impacts. Combining what we can see on the moon with what is exposed at depth on Earth by erosion and drilling, gives us a vision of how a really large meteorite impact behaves.

So what happens upon impact? The meteorite itself mostly disintegrates and partially vaporizes, and the gas and particles get partially blown back into space, taking some of the earth rock with it and creating a crater. Beneath the crater floor the released energy momentarily compresses the rock and shatters it to a depth of several miles.

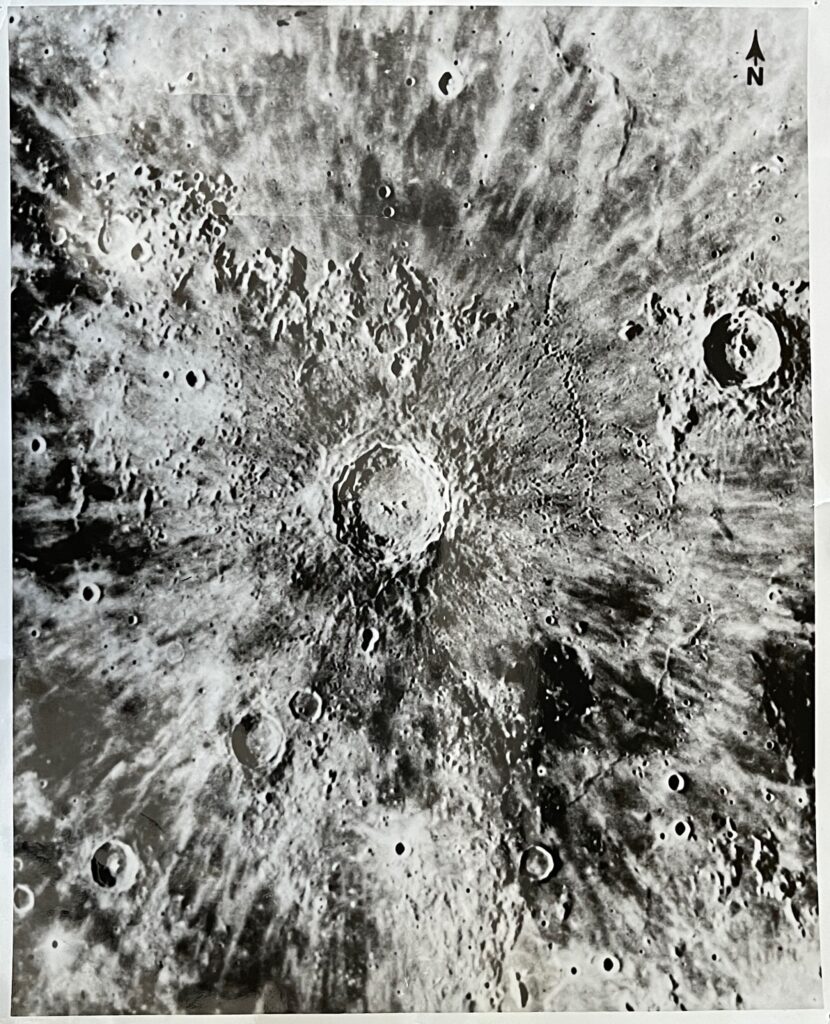

But when this incoming pressure is released a minute later, the compressed rock rebounds and occupies more space than it did originally, and expands into a ragged dome rising up in the floor of the crater. The rim rock around the edge of the crater is bent upward then a layer of debris sprays outward and upward. Some of that debris falls back into the crater while the landscape is still quivering with shock waves, and on the steep sides of the crater this layer slumps or landslides, forming a set of terraces along the crater wall. If we look to one of the most recent big craters on the surface of our moon’s near side, we can see most of the above features preserved.

Copernicus shows us a clear splatter pattern of younger, lighter rays of debris spreading out across the dark older background. The raised rim of this crater is about 50 miles across, so the area of the photo is similar to the area of Iowa. The north side of the debris layer extends out as lobes — miles thick — casting shadows onto the older surface. Landslides within the crater form terraces around the crater walls. The top of the rebounded center of the crater creates mountain peaks several miles high, protruding out of the deep layer of fallback debris that fills the crater floor. Younger, smaller craters dot the rayed debris field.

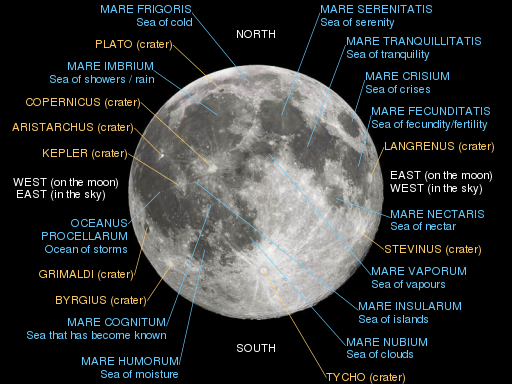

Using a pair of ordinary binoculars (and maybe sunglasses), and leaning against something for stability, anyone looking at the full moon can also see the much larger, partially round, flat areas which dominate the near side. These were labeled “seas” by the early astronomers and the old names have stayed with us even though we now know these flats, such as the Sea of Tranquility, seem to be mostly made of hardened lava, covered with a variable amount of dust and debris from younger impacts.

It is still not clear whether these seas of molten rock were entirely created from the energy of enormous meteor impacts, or whether the core of the moon was plastic or liquid during its early history and some flooded the deeper craters. Seismographs planted on the lunar surface a half-century ago to answer this question indicate that at present the core of the moon is solid rock, not the soft and plastic stuff we call the mantle that we have beneath us here on our home planet.

Next time, we’ll look into a couple of very large meteor impacts on Earth, including one that dramatically changed the direction of the evolution of life, followed by a deeper dive to discover some big impacts here in Iowa.

Tags: copernicus, earth, impacts, lava, Lon Drake, meteorite, molten rock, moon, nasa, outer space, seismograph, space