Aversive Conditioning in the Natural World

Everyone knows that monarch butterflies are protected from birds to some extent by the toxic chemistry they inherit from caterpillars who preceded them, who in turn, got it from the milkweed plants they ate. Likewise in the tropics, numerous species of poison frogs are flamboyantly colored and patterned to advertise that there will be consequences if a predator eats them. But these examples of protective coloration also indicate that predators do eat a few of them in order to learn the lesson. Thus, the individuals can be viewed as potentially sacrificial to protect their species. This is a quite common theme in nature.

At night, protective coloration doesn’t mean much because colors are reduced to shades of gray. When I am deer hunting in my tree stand in the late afternoon, I can see another hunter a half-mile away in her orange vest. When hunting ends for the day, I sometimes deactivate my firearm and linger just to watch the deer, foxes and others who now feel more free to move about. There is a magic moment when the diminishing light levels no longer reflect hunter orange, and the other hunter disappears into the gloaming.

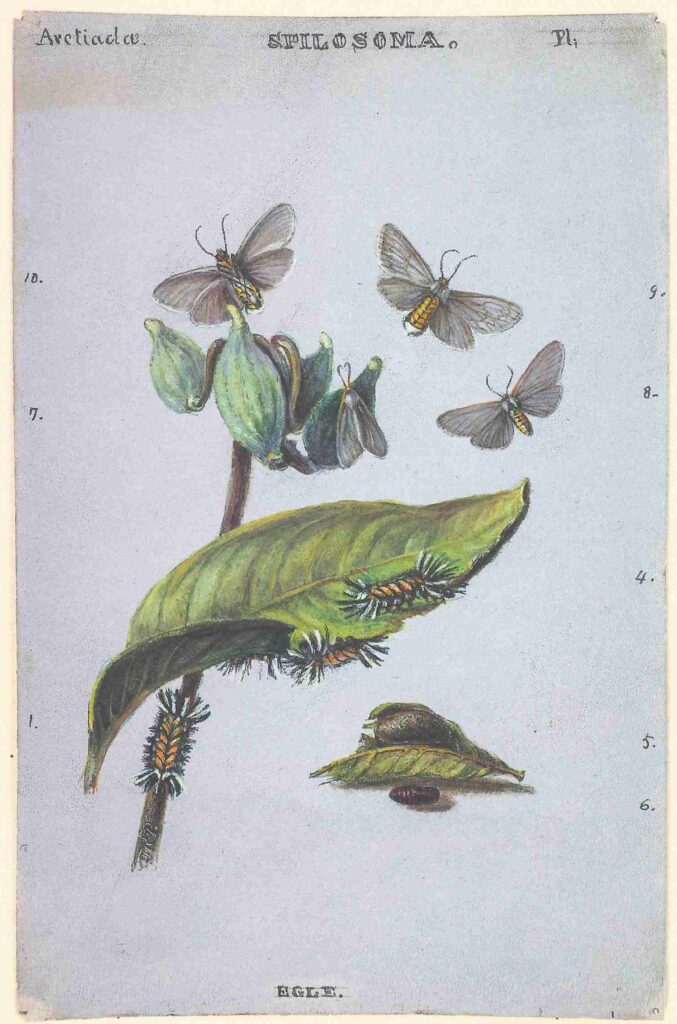

As you know, bats hunt moths at night — not by sight, but by sound — using echolocation. The milkweed tussock moth uses the same general survival strategy of aversive conditioning as the monarch. Its caterpillar also feeds on milkweed, creating a toxic moth, which is an ordinary whitish gray because color will not advertise its toxicity at night. Rather, the moth makes a little squeaky chirp, which bats can hear. After eating a couple of them, the bat gets sick, decides that chirping moths are not desirable cuisine, and leaves them alone.

Painting of the milkweed tussock moth and its caterpillar by Titian Peale about 200 years ago featured in “The Butterflies of North America: Titian Peale’s Lost Manuscript.”*

The bold markings of the skunk — black for day and white for night — also advertise that it should be left alone, and most potential predators do, except for great horned owls, who don’t seem to care, and dogs, who have had the wildness bred out of them and don’t learn from their first harsh encounter. I was once standing still in the twilight when a great horned owl came skimming along the edge of our hedgerow and glided by within a few feet of me. The smell of skunk that trailed behind was awful, and I wonder whether it serves some protective function, such as keeping predators away from the owl’s nest or killing parasites. In popular slang, the smell would “gag a maggot” and I wonder whether it actually does.

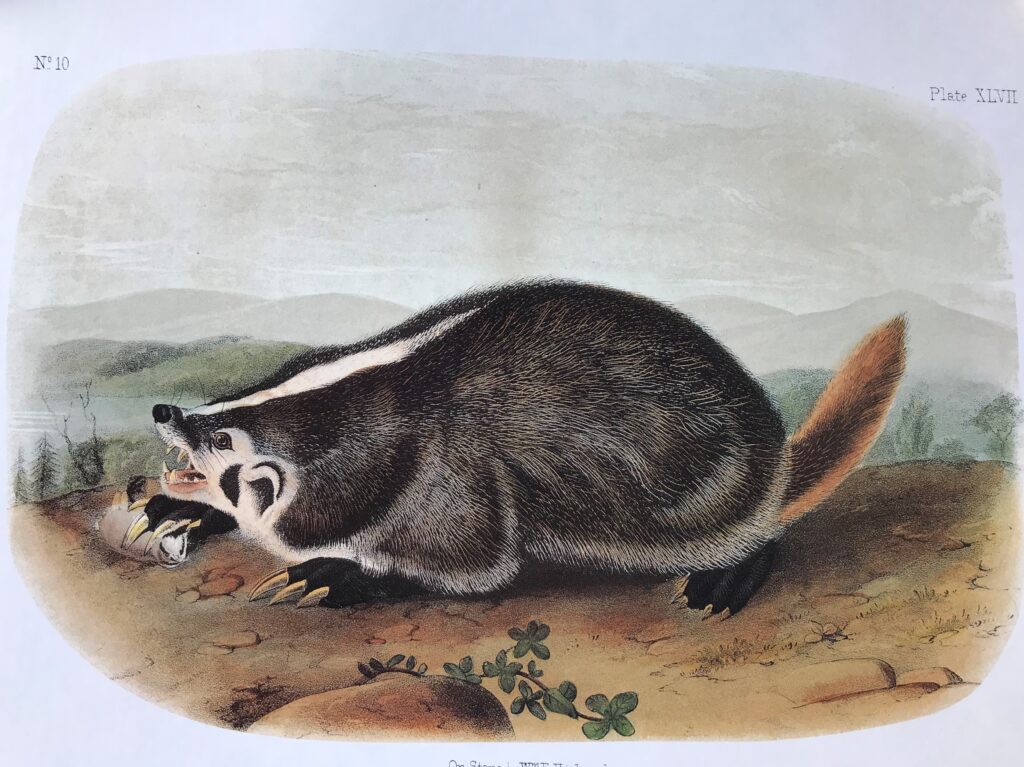

The skunk’s mustelid cousin, the badger, is also marked with a bold body stripe, which advertises that it is a fierce predator who digs and burrows for a living. This niche overlaps a lot with that of the black bear who also does a lot of digging, tearing apart rotten logs and flipping over rocks. When the bear meets a badger who is already mining a productive spot, the bear usually just moves on elsewhere, in spite of being much larger than the badger.

The American Badger, from “Audubon’s Mammals: The Quadrupeds of North America.”

Note that the warning stripe is only on the forward portion of its body because the badger faces its enemies head-on with its backside buried in the hole it digs in a moment. For more about Audubon’s Mammals, the complete and unabridged reprint of Audubon’s “Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America,” see my book review from Jan. 4, 2018.

Somewhere in our distant past, predators perhaps learned to avoid the lightweight bipeds who were endurance runners and carried spears. And today, even the big predators need to learn to avoid the same bipeds who now carry firearms instead of spears. Wolves have pretty much figured this out already. Next week, lets explore a practical application of aversive conditioning for conservation.

*Titian Peale’s lifetime (1799–1885) was steadfastly devoted to the study of North American butterflies and moths, and he always intended to produce the definitive volume on the subject based mainly upon his extensive field observations and detailed drawings. But the requirement of earning a living plus family disasters interfered and he died poor, without his manuscripts published. They resided in the Peale family for decades, who then gave them to the American Museum of Natural History nearly one hundred years ago, where they resided in the rare book collection. In 2015, the museum published selected drawings and notes as a book titled “The Butterflies of North America: Titian Peale’s Lost Manuscript” (Abrams, 255 pages). In my opinion, if he had been able to complete his goal in his lifetime, he would be as well known today for his butterflies and moths as John James Audubon is for his birds.

Tags: Audubon, aversive conditioning, badger, Butterflies of North America, John James Audubon, Lon Drake, Quadrupeds of North America, skunk, Titian Peale