A Little History of the Kayak

Much of what we know today about the history of the American kayak we owe to two people: Edwin T. Adney and Howard Chappelle.

Adney spent a lifetime studying northern Native watercraft, mainly the birchbark canoe. He interviewed the last of the Native builders at work, took photos, drew blueprints, built models and carried on an extensive correspondence with museums that had examples. Inspection of Adney’s estate following his death in 1950, revealed that his lifetime of research was in complete disarray. No one wanted to deal with it and for years the “Adney Collection” seemed to have a dumpster destiny.

However, Howard Chappelle of the Smithsonian, had been doing his own research on Native kayaks and umiaks of the far north country and saw an opportunity to combine his studies with Adney’s into a publication, and in 1964, the U.S. Government Printing Office released “The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America” by the two authors. Skyhorse Publications followed up with a printing in 2007. My copy is on cheap newsprint and the photo quality is very poor. Today’s note relies extensively upon this book, which is also the source for our illustrations.

However, Howard Chappelle of the Smithsonian, had been doing his own research on Native kayaks and umiaks of the far north country and saw an opportunity to combine his studies with Adney’s into a publication, and in 1964, the U.S. Government Printing Office released “The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America” by the two authors. Skyhorse Publications followed up with a printing in 2007. My copy is on cheap newsprint and the photo quality is very poor. Today’s note relies extensively upon this book, which is also the source for our illustrations.

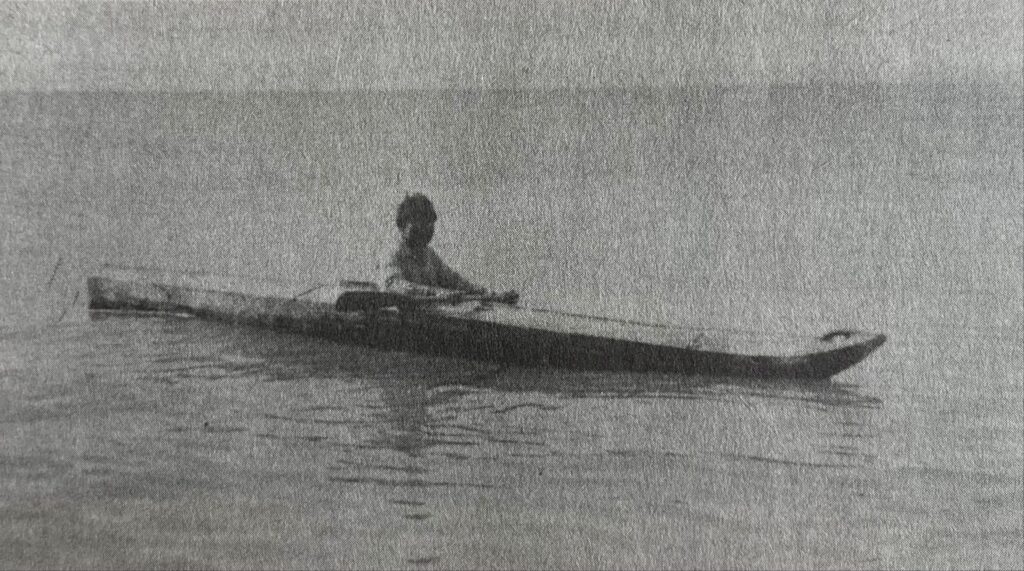

The Native kayak was a hunting boat, built for speed sometimes adequate to run down and harpoon a seal or walrus. Consequently, the shape was very long and slender, and pointed to slice readily through small waves. They were also very lightweight as part of the speed requirement. Modern recreational seagoing kayaks, while now made of plastic, still very much continue to copy this basic design.

Living in a coastal environment with few trees, Natives carefully carved the framing members from driftwood, which was mainly pine, spruce, aspen and willow species. Before Europeans arrived with metal screws and bolts, the vertical ribs and horizontal strakes were joined with carved joints tied or laced together with sinew or leather.

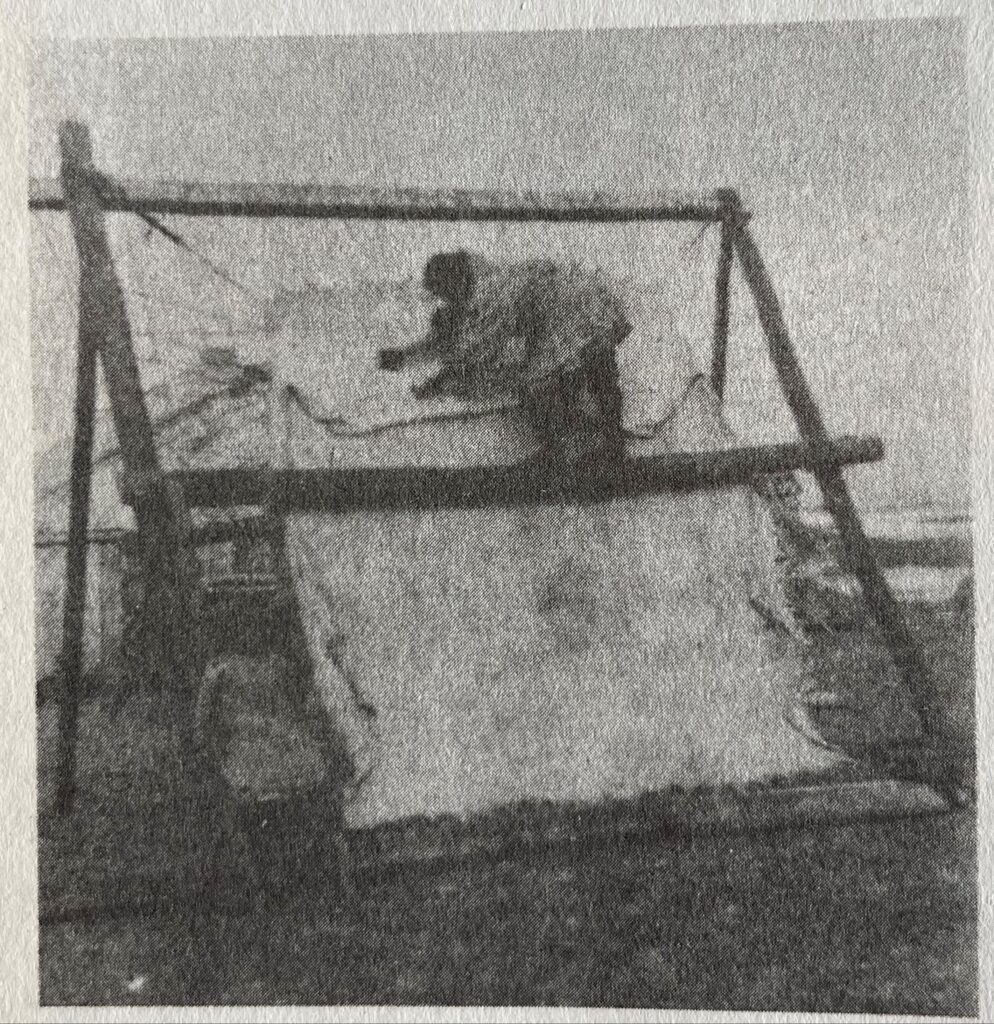

The outer covering was oiled leather, often seal skins, which the women joined with a blind stitch that was waterproof. Walrus hide intact was too thick and heavy, but it could be split into two layers and the thinner inner layer oiled and used. Where caribou migrations reached the coast, those hides were sometimes prepped and used.

The long, double-bladed paddle we today consider standard for a kayak was not necessarily the choice of Native People. Many used a single-blade version more similar to what we today consider to be a canoe paddle, see photo above. Hunters also often carried a single-blade version with a short stubby handle, which they sculled stealthily on the side opposite a dozing seal.

Early European visitors sometimes reported that kayaks carried a tiny sail. This was a misunderstanding, because hunters stalking seals sometimes put up little rectangular flaps to hide their faces behind as they pretended to be a log drifting by.

The “Eskimo roll” or “kayak roll” was widely practiced by the Natives and each village seemed to have a couple of guys acknowledged to be especially adept. Europeans recorded that in some cases, instead of taking a big curling wave head-on, a skilled hunter would roll under the wave and pop up on the quiet backside with only his hands and face wet. There were numerous versions of the method, depending upon the demands of the moment.

For example, if a hunter got flipped because his right arm got tangled in the harpoon line with a seal on the other end, his response depended upon which way the seal was trying to pull him, how strong it still was, whether the line was knotted or just wrapped around his arm, etc. The deck of a kayak had a little toolkit spread out before the hunter, with everything secured with leather thongs.

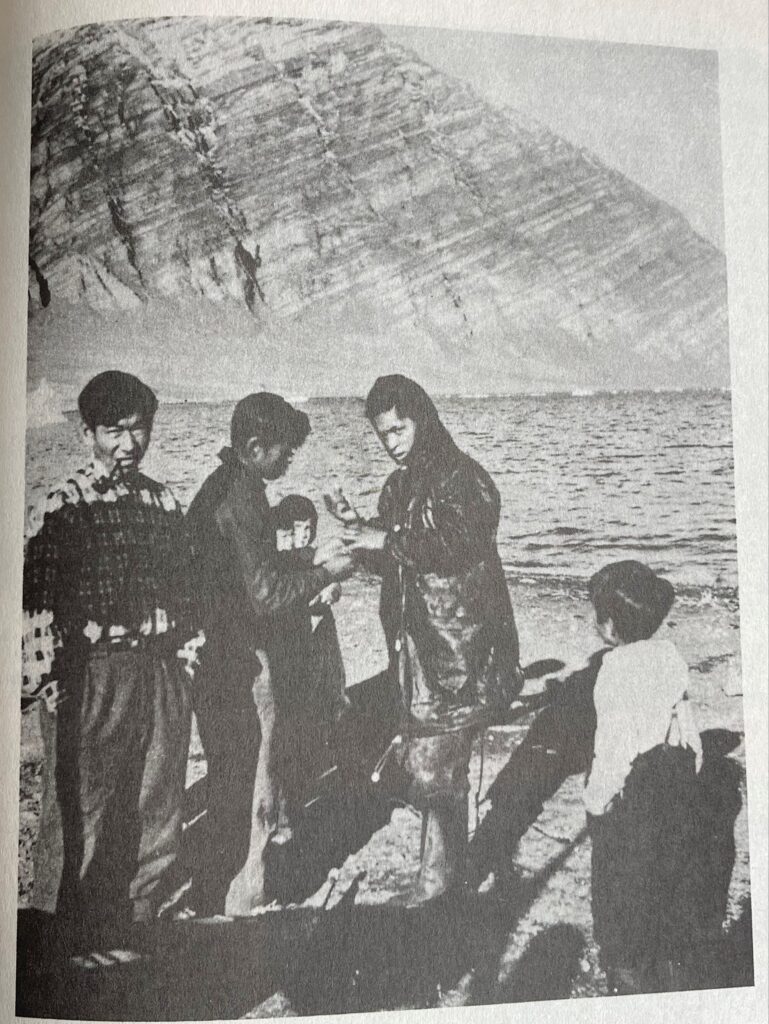

Jonas Malakiasen, preparing for a roll demonstration, West Greenland 1959, Adney and Chappelle. When his jacket is snug against his face, wrists and cockpit hoop, he can roll without getting water inside his kayak.

Chappelle does not address the arrival of the small harpoon gun, which I think was used briefly by kayak hunters. It was a short-barreled 10-gauge shotgun rigged to fire a wood-shafted, steel-tipped harpoon. Today, these harpoons and hunting kayaks are found together as wall displays in Alaska roadhouses, and leave me the impression that they vanished from the hunting scene together, replaced by modern boats with motors and high-powered rifles.

Tags: Adney Collection, Alaska, Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North America, Edwin T. Adney, Howard Chappelle, Indigenous People, Jonas Malakiasen, kayak, kayak hunting, kayak roll, Lon Drake, Native People